RESEARCH/RESPONSE: AHURI’S Report

AHURI in partnership with The Housing for Health Incubator and other collaborators released a 107 page report in November 2021, “Sustainable Indigenous housing in regional and remote Australia”.

Read Time: Approximately 11mins

The report focusing on ‘Sustainable Indigenous Housing’ argues ‘sustainability’ as a term which means “the capacity of housing to confer positive health and wellbeing outcomes for householders, where housing stock is consistently maintained at high levels over time and is designed with current and future climate change challenges in mind.”

The report covers a broad range of content over its chapters. From life-cycle costing, repairs and maintenance programs including an exemplar program on the APY lands, Housing Repairs and maintenance data and costs and modelling of climate change forecasting to important anticipated impacts on housing performance and resilience moving forward.

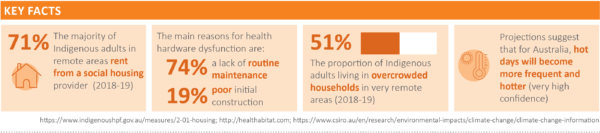

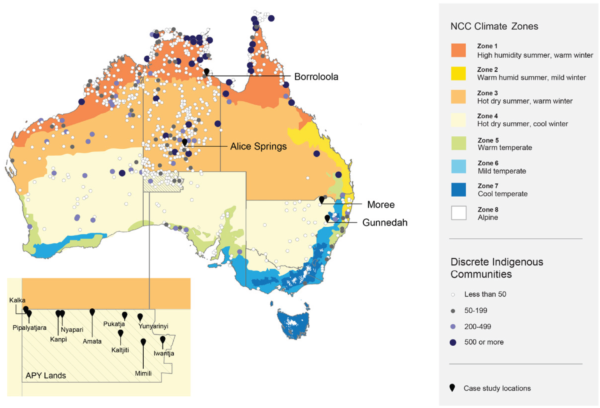

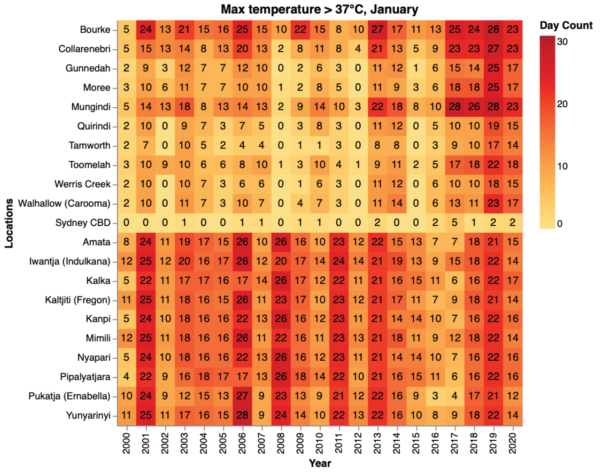

The report clearly explains that future climate change will increase the severity and regularity of extreme weather events and will erode the habitability of certain parts of Australia. People will experience higher indoor temperatures and increased risks of overheating, with maximum temperatures consistently higher across all modelled scenario climate zones in the report (Tropical; Borroloola NT, Arid; Alice Springs NT and hot/mild; Moree NSW), by up to 7°C.

Infographic of the AHURI report produced by The Housing for Health Incubator

“Without action to stop climate change, people will be forced to leave their country and leave behind much of what makes them Aboriginal. Climate change is a clear and present threat to the survival of our people and their culture.” (Allam and Evershed 2019)

What is Healthabitat’s interest in the report?

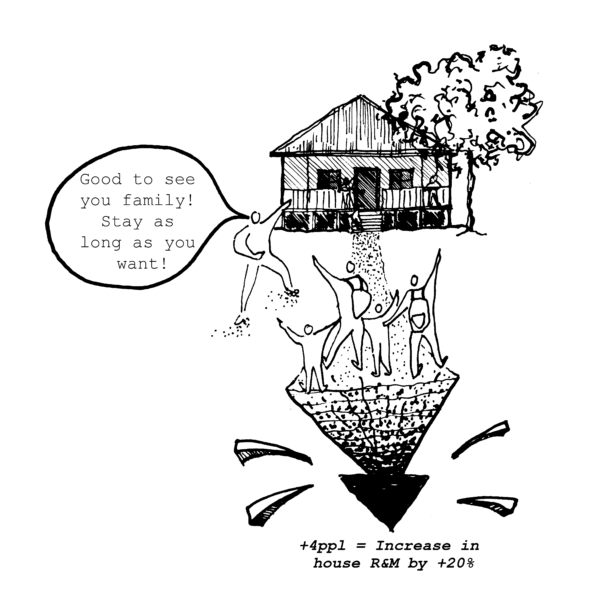

Healthabitat found the statistics and data from the impacts of crowding at the house level both fascinating and alarming. Although the health and house impacts of crowding are obvious, including for example hot water system volume to hot showers available and sewage system capacity to number of toilet users, the hard data in this report allows the impacts of crowding to be more broadly and quantifiably realised; for example, for every two additional people added to a household, “operating and maintenance costs increase by 10 per cent “.

This quantitative information with $ figures captured in the report allows us to understand the implications of remoteness, the direct impact on repairs & maintenance requirements and increased loads on heat gain and cooling consumption crowding has on houses, people and resources.

As the reports emphasises, although there may be changes in the way people use remote communities, many people will continue to visit and live on country and so it is important Indigenous housing retains a focus on its level of ‘sustainability’, on effective health hardware and maintenance programs.

What are some issues the report shows us?

- Indigenous housing stock and Repair & Maintenance programs are generally poor, with serious housing shortfalls contributing to crowding

“Current regional and remote Indigenous housing stock is unable to provide consistently healthy and comfortable indoor environments. There seems to be an unstated assumption that what is practically sustainable for governments and housing providers is the undersupply of substandard housing serviced by inconsistent repairs and maintenance (R&M) [programs].”

The average age of Aboriginal Housing Office (AHO) properties throughout NSW is about 35 years. The current condition and original design of such properties, termed ‘hot tin boxes’, underpins their poor thermal performance. Healthabitat’s data in the report concludes that standard Indigenous housing performs poorly due to, “little to no insulation, with only 26% of the audited houses having wall insulation and 37% roof insulation” and “only 33% having a cooling system installed, of which 42% were fans.”

“New South Wales is experiencing an under-supply of social housing. Using forecast estimates derived from 2016 ABS Census data, the AHO indicates that in 2017, 39,494 houses were required to fulfil Aboriginal housing demand, while 28,638 properties were available (AHO 2018a). The supply gap of 10,855 properties is equivalent to 27.5 per cent of total demand. At current rates of acquisition and construction…the proportion of unmet demand is expected to increase to 47.1 per cent by 2031, a shortfall of 30,124 properties”.

Metropolitan housing costs vary greatly from housing in remote communities, with cost being a largely prohibitive factor in housing construction, supply and maintenance;

- The metropolitan costs for responsive maintenance costs (costs from unplanned or emergency maintenance) are almost 2 times than planned maintenance programs, where this increases by 7 times in a remote community

- Remote housing construction is 1.7 times greater than capital city costs

- Very remote housing construction is two times greater than capital city costs

- Remote housing operating and maintenance costs are three times greater than capital cities.

- Very remote housing operating and maintenance costs are three times greater than remote regions.

- There is a lack of planning for housing resilience from the impacts of climate change

This report finds “attention to climate change is not yet a feature of Indigenous housing and infrastructure agreements, with inadequate funding and attention paid to climate preparedness in new builds, refurbishments and retrofit programs… Current consideration largely extends to the potential provision of split system air conditioning units for existing stock, meeting the minimal requirements of state/territory environmental design measures for new houses and residential tenancy acts for existing houses.”

Current state and territory and federal housing policies and bilateral agreements do not mention climate change nor adaptive measures for extreme weather events, and national schemes to improve dwelling thermal performance have no legal enforceability. “The Australian Government appears to have stepped away from regional and remote Indigenous housing provision, and state and territory governments have not developed comprehensive and well-funded strategies”, yet “In 2021, Infrastructure Australia (2021) included ‘Remote housing crowding and quality’ on its list of ‘High Priority Initiatives’. It highlights a range of required actions to reduce crowding in line with Closing the Gap goals.”

The report shares an exception in this policy gap; “The Far North and Outback SA Climate Change Adaptation Plan identifies essential services, transport and infrastructure and community health, safety and wellbeing as three of eight key sectors to prioritise for adaptation planning (RDA Far North SA 2016). It proposes that initial attention be paid to enhancing current initiatives and retrofitting existing buildings, with a five to ten-year focus on increasing the resilience of the built environment, including by constructing community facilities to serve as heat refuges and promoting climate-sensitive building designs to support preventative health.”

The report proves the need for planning can not just stop at houses. “All scenarios [modelled by the report] register a dramatic increase in energy consumption [due to the required increased use of active cooling systems in houses], revealing a need for future implementation in the energy grid, production and provisions.”

- Occupancy level (crowding) is a major factor in determining housing performance, particularly in relation to indoor comfort and stress on Health Hardware

“The 2014–15 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS) showed that more than one-third (38%) of remote Indigenous people over 15 years lived in crowded conditions, compared to 13 per cent elsewhere.” The report also showed that for every two additional people added to a household, “operating and maintenance costs increase by 10 per cent “.

Crowding was identified as another cause of accelerated wear and tear, where the report’s modelling demonstrated increased crowding as a thermal health and comfort issue, “Simulations highlighted the higher the number of occupants, the higher the energy consumed, regardless of the design model, the type of cooling system or ventilation scenario.” This means that occupancy will continue to be a major driver in determining the cooling needs of Indigenous housing.

In the reports modelling, anticipated cooling loads in houses proved a primary concern with tropical climate results proving crucial. Cooling-related energy consumption was almost three times higher in the tropical climate scenario than the hot/mild climate and twice the arid climate. “Occupancy density impacts the frequency of overheating, with higher frequency when the house is not equipped with an active cooling system in all rooms”, often cooling systems are in one main living area causing all the tenants to crowd in to stay cool.

What are solutions & ways forward?

- There is value in ‘improved housing design’ and refurbishments for passive cooling and heating to existing housing stock to minimise the effects of crowding

A project carried out by Healthabitat in 2011, ‘Cool houses in warm climates’, used the data logging of 4 houses in Central Australia to show an 8 degree reduction in peak summer temperatures as a result of passive cooling refurbishments.

“Effective design, high quality construction and the installation of appropriate technologies can reduce the proportion of life-cycle costs committed to operating and maintenance expenditure.” Where, “The required expansion of housing supply can be augmented by refurbishment programs that expand the size and amenity of existing houses (for example, through the addition of bedrooms and wet areas). However, consideration should be given at the household level to residents’ preferences for sleeping arrangements and to whether existing retrofit programs encourage crowding, such as through the provision of single air conditioning units in living areas”

All scenarios modelled without mechanical ventilation presented indoor environments that were unhealthy for the occupants with temperatures that didn’t fall below 26C. This shows “that, in the future, Indigenous housing must either rely on fully functioning active cooling systems or better and more high performing construction and architectural systems to provide decent living environments.”

- Higher standards for housing construction and specifications informed by climate change requirements are required along with anticipated maintenance regimes to improve climate resilience

The report considers “sustainable houses as those that have been built with structural integrity and robust materials, given climate and household compositional requirements and which are maintained in good working order through effective property maintenance systems. The sustainable R&M programs necessary for quality housing are those that are reliably resourced and regularly implemented, are responsive to householder concerns and that provide maximal opportunities for community engagement and local employment.”

“Ikpo (2009) refers to developing maintainability indexes of buildings as a way of measuring their likely performance. This requires the specification of materials for particular climate requirements and anticipated maintenance and replacement needs.”

- There is value and importance in investing in Health hardware and cyclical R&M programs

The report estimates…”of total life-cycle costs, construction costs represent 62 per cent, operation and maintenance comprises 35 per cent and disposal comprises 3 per cent of total life-cycle costs. In very remote regions 75 per cent of the life-cycle costs of a dwelling is related to operating and maintenance costs.” This shows us that “Construction is a relatively minor component of the total life-cycle costs of remote and very remote Indigenous housing compared to operations and maintenance over time… where one reason maintenance has not been considered a priority intervention is the fact that it is considered an expense not an investment.”

The reports’ data indicates, “the median cost of emergency maintenance and repair activities is 75 per cent higher than planned activities, while responsive activities which are non-emergency are 50 per cent more costly than planned. At the extremes, some maintenance and repair activities are up to 20 times higher in an emergency situation than in a planned maintenance package. (Nous Group 2017: 25)”

The report also declares, “Effective early interventions in key failure points in health hardware (the amenities required to enact health-conferring practices) will assist in extending the habitability of even highly degraded housing stock to alleviate the health impact of crowding”.

Healthabitat encourages cyclical maintenance to be a focus, as early as the design phase and to be seen as an investment and essential for improving health, regardless of an increase in the quality of housing stock. Houses that are not maintained fall out of commission quickly and do not provide their basic function of supporting the health and wellbeing of tenants, which then causes crowding in houses which do have functioning Health Hardware. The long-term cost of property management is decreased by having a cyclical maintenance program in place, which preserves functionality and increases the life of housing assets.

- Focusing on the relationship of the house to the yard can aid crowding inside the house

Verandahs are valuable living space at about a third the cost of internal house areas. Well sited and furnished verandahs that are usable in wet weather are valuable for reducing crowding as they become useful spaces for cooking, drying clothes, guest sleeping areas and shaded play areas for children.

Nganampa Health Council emphasises in Chapter 3, the relationship between the house and the yard as central to the UPK program. “The removal of Buffel grass from in and around yards is an important hazard reduction activity, relating to the fire safety components of Healthabitat’s Housing for Health: The Guide. Such work also reduces crowding because you’re making the yard more liveable. An interview in the report talks of the value of the yard, “You could have 15 people in the house and functional crowding was three groups of five people … If the yard was well furnished, and yard furniture was well kept, you had five groups of three people because two groups were outside.”

- Future focuses on infrastructure improvement and hence an increased high quality housing supply will reduce crowding

In the context of reducing the impacts of crowding, by providing new stock, adding space, and ensuring functioning health hardware to relieve pressure on houses, the report emphasises bathroom and laundry facilities, using high quality componentry and design standards should be a focus.

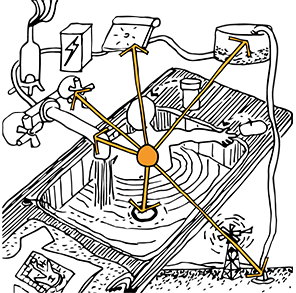

Nganampa Health Council also explains in the report it isn’t as simple as just building more houses, as an increase in community residents increases the stress on municipal services infrastructure such as water supply, sewage processing and power generation. Stress is further placed on other community services including “… on the store that has to get food in, the clinics that have to look after people and the police that have to police even more people now. And so, as long as those infrastructures and the services coincide with expanding housing, it’s going to work, but it won’t work if everything else doesn’t expand with the housing population.“

Thanks to the Housing for Heath Incubator for their work in compiling the report. Their work in broadening the conversation around the link between housing and health and providing quantifiable data to continue to support the argument of the negative impacts of crowding on the health of people is important. The report emphasises the importance of investing in and ensuring Indigenous housing is ‘sustainable’ as the climate continues to change into the future.

Reference Images

NCC Climate Zones with Locations of Indigenous Communities

Higher Maximum Temperatures Sustained for Longer Periods: Graph 2000-2021