Report – Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage

Healthabitat suggests the NATSIHS survey which forms some of the data used in the Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage report could use some tweaking.

The Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage 2020 report was released in December by the productivity commission. The report measures the wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people against 52 indicators across a range of areas including governance, leadership and culture, early childhood, education, economic participation, health, home environment and safe and supportive communities.

There are some encouraging signs buried in the 4000+ page document, plus a few tweaks that Healthabitat would suggest.

The report addresses three aspects of the home environment;

- Crowding in housing

- Rates of disease associated with poor environmental health and,

- Access to clean water and functional sewerage and electricity services

Crowding in housing

From the report;

Safe and secure housing is essential for people’s wellbeing. Overcrowded housing can have detrimental effects on health, education and social outcomes, including by jeopardising personal safety and security.

- Overcrowded housing is an environmental factor that contributes to higher rates of preventable and infectious diseases2 (Hall et al. 2020; Harford-Mills, MacRae and Drew 2019; Lowell et al. 2018; The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners and NACCHO 2018) and can exacerbate the severity of illnesses and need for hospitalisation (Quilty et al. 2019).

- Crowding is associated with poor cognitive development and poorer reading test performance among elementary and middle school children (Brackertz 2016). Overcrowded housing is also linked to lower levels of school attendance and educational achievement (Lowell et al. 2018; Silburn et al. 2018; Wilson 2013).

- Crowding from visitors staying extended periods can occasionally lead to antisocial behaviour, which can result in higher levels of family violence (Moran et al. 2016), and sexual abuse against children can be due to opportunistic behaviour by additional adults in the house (Blagg et al. 2018).

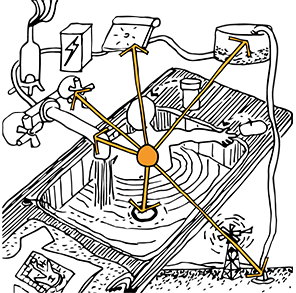

Crowding is measured using the Canadian National Occupancy Standard (CNOS) which essentially uses room number as the key measure. Healthabitat would like to see house function included as a key indicator, as house size alone does not improve crowding. Healthabitat has written about solutions to crowding before.

Rates of disease associated with poor environmental health

From the report;

- Hospitalisation rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people for environmental health diseases are more than double those of non-Indigenous people, and the gap has widened. The largest gap was in rates of influenza and pneumonia; rates for non-Indigenous people have decreased in recent years, whereas rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have continued to increase.

- Improving the quantity and quality of housing, ensuring the availability of functioning health hardware and increasing access to health care services are all strategies to address the risk factors for environmental health diseases for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Crowding and poor housing quality (including poor health hardware) are linked to higher rates of environmental health diseases. Crowding can lead to deterioration in housing quality and breakdown in household facilities (such as toilets and washing machines) that are important for maintaining good hygiene (Ali, Foster and Hall 2018). Overcrowded and poor quality housing have been linked with higher rates of gastrointestinal, skin, ear, eye, and respiratory illnesses for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (Ali, Foster and Hall 2018; May, Bowen and Carapetis 2016). Furthermore, crowding can mean that infectious diseases, once present in a community, can circulate more rapidly (May, Bowen and Carapetis 2016).

Enhancing the quality of housing is also important in improving environmental health and reducing the rates of associated diseases. This includes installing good quality health hardware and ensuring regular maintenance of housing and health hardware (Standen et al. 2020).

It is heartening to see house function and health linked as well as regular maintenance of good quality health hardware as part of the discussion. Healthabitat hopes to see this as part of future work in Aboriginal housing.

Access to clean water and functional sewerage and electricity services

From the report;

- The quality of housing can be improved for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander households by investing in suitable design and construction, reducing crowding and ensuring regular repairs and maintenance.

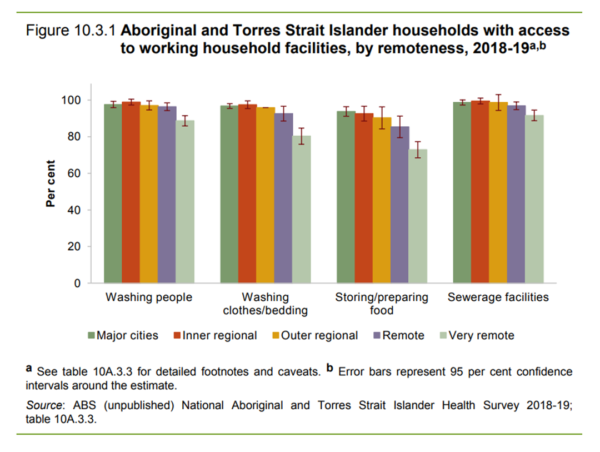

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander households living in housing of an acceptable standard is defined as the proportion of households with four working facilities and not more than two major structural problems. The data source for this measure is the ABS National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey (NATSISS)/National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey (NATSIHS), with the most recent data for 2018-19. The data from the NATSIHS are ‘self-reported’ and are based on the respondent’s view of their house and its functionality.

There were differences in the question methodology between NATSISS 2002, 2008, 2014-15 and AATSIHS 2012-13 when asking about functional household facilities. In 2002, households were asked about the presence of working facilities and in 2008, 2012-13 and 2014-15 households were asked about the absence of working facilities.

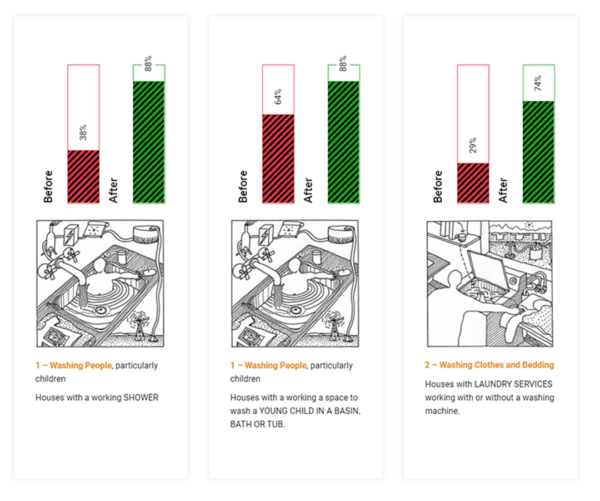

Healthabitat agrees with the first point above, however, the NATSIHS survey might need a second look. Above is the graph provided showing “working” household facilities. Access to facilities for washing people is, at it’s lowest, about 90% from about 350 houses based on asking residents. Healthabitat’s data from over 9300+ houses nationally shows that before a Housing for Health program only 38% of houses had a working shower. This is based on local teams physically testing the shower taps, shower rose, water pressure and drainage. Perhaps the NATSIHS surveyors were lucky enough to go to houses that had recently had a Housing for Health program completed where the function of facilities to wash people is up to 88%.

Data from all 9300+ houses nationally that Healthabitat has surveyed since 1999. This data is collected using a standard test of over 250 items in each house. It does not rely on anecdotal evidence that washing facilities work but physically tests taps, drainage, water pressure and water temperature.

Healthabitat would suggest that the NATSIHS data should be reviewed based on testing health hardware rather than relying on anecdotal evidence from open-ended questions open to interpretation. There is still a long way to go to improve Indigenous housing in this country, Healthabitat looks forward to seeing real change for our Indigenous communities Australia wide.

References

(from Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage report)

Ali, S.H., Foster, T. and Hall, N.L. 2018, ‘The relationship between infectious diseases and housing maintenance in Indigenous Australian households’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 15, no. 12, p. 2827

Blagg, H., Williams, E., Cummings, E., Hovane, V., Torres, M. and Woodley, K.N. 2018, Innovative Models in Addressing Violence Against Indigenous Women: Final Report, 01/2018, Horizons, ANROWS.

Brackertz, N. 2016, Indigenous Housing and Education Inquiry: Discussion Paper for Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet, May, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, Melbourne.

Hall, N.L., Memmott, P., Barnes, S., Redmond, A., Go-Sam, C., Nash, D. and Frank, T.N. 2020, Pilyii Papulu Purrukaj-ji (good housing to prevent sickness): A study of housing, crowding and hygiene-related infectious diseases in the Barkly Region, Northern Territory, commissioned from the University of Queensland for Anyinginyi Health Aboriginal Corporation, Tennant Creek, Northern Territory, Queensland, p. 76

Lowell, A., Maypilama, Ḻäwurrpa, Fasoli, L., Guyula, Y., Guyula, A., Yunupiŋu, M., Godwin-Thompson, J., Gundjarranbuy, R., Armstrong, E., Garrutju, J. and McEldowney, R. 2018, ‘The “invisible homeless” – challenges faced by families bringing up their children in a remote Australian Aboriginal community’, BMC Public Health; London, vol. 18.

May, P.J., Bowen, A.C. and Carapetis, J.R. 2016, ‘The inequitable burden of group A streptococcal diseases in Indigenous Australians’, Medical Journal of Australia, vol. 205, no. 5, pp. 201–203.

Quilty, S., Wood, L., Scrimgeour, S., Shannon, G., Sherman, E., Lake, B., Budd, R., Lawton, P. and Moloney, M. 2019, ‘Addressing profound disadvantages to improve Indigenous health and reduce hospitalisation: A collaborative community program in remote Northern Territory’, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 16, no. 22

Standen, J., Morgan, G., Sowerbutts, T., Blazek, K., Gugusheff, J., Puntsag, O., Wollan, M. and Torzillo, P. 2020, ‘Prioritising housing maintenance to improve health in Indigenous communities in NSW over 20 years’, International Journal Of Environmental Research And Public Health, vol. 17, no. 16, p. 5946.