Report – Housing for health, 20 years on…

A peer-reviewed paper has been published looking at 20 years of Housing for Health projects in NSW.

Titled: Prioritising Housing Maintenance to Improve Health in Indigenous Communities in NSW over 20 years

Healthabiatat has summarised some of the report below…

Housing and health agencies should collaborate more closely on social housing programs and ensure programs are adequately resourced to address safety and health issues.

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognises poor housing as one of the main social causes of ill health [1,2] and extensive evidence has demonstrated improvements in health associated with improvements in housing and living environments since the late 1800s [3–5]. While Australia is an economically developed country with a high standard of living [6–8], poor housing in Aboriginal communities continues to be linked to the compromised health status of Aboriginal Australians since early last century [9–18].

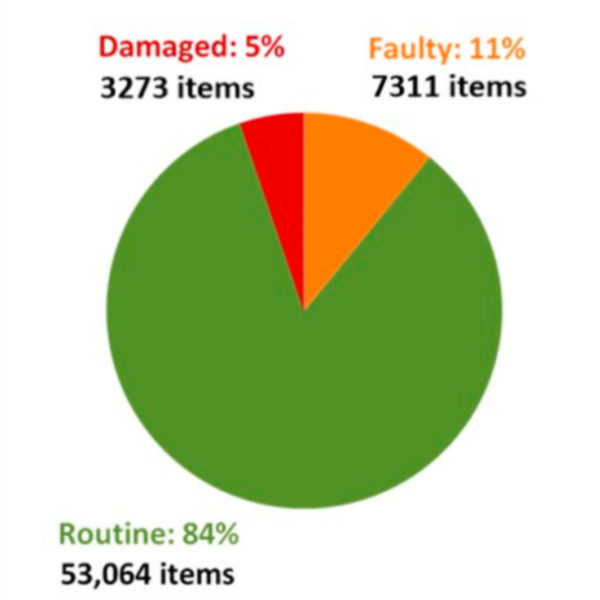

There are some widely held beliefs about social housing being poorly looked after by the tenants, so the tradespeople are required to identify and record the cause for each repair being either:

• Routine (maintenance reasonably expected in a house);

• Faulty (the item isn’t present or installed incorrectly), or

• Damage (by people, and not by ants, vermin, poor water quality or other factors outside of the residents’ control).

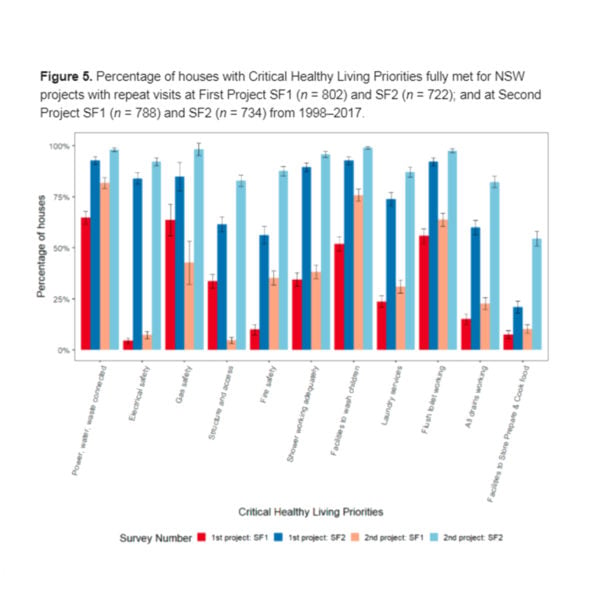

Based on the literature, Healthabitat developed a practical implementation of evidence-based practices that support healthy living [11,22]. These included 11 Critical Healthy Living

Priorities (CHLPs) which are reported in this analysis:

1. Power, water, and waste connected

2. Electrical safety

3. Gas safety

4. Structure and access

5. Fire safety

6. Shower working adequately

7. Facilities to wash children

8. Laundry services

9. Flush toilet working

10. All drains working

11. Facilities to store, prepare and cook food

Each CHLP is measured by assigning a set of data items from the survey. For example, for a house to enable residents to wash effectively and to maintain hygiene and health, a shower in a house requires the following minimum seven items to be functioning: hot water; cold water; hot water at a safe but effective temperature; hot and cold water taps; a shower hose and adequate drainage [9].

The HfH program has reached around 70% of houses in the NSW Aboriginal community housing sector from 1997-2017.

At SF1(Survey Fix One) …only 39% of all houses had all items in the shower working and two thirds of houses had a place to wash a small child with all hardware working (such as a bath, large basin or laundry tub with washing machine by-pass).

Figure 4 presents data on the reasons tradespeople recorded for repairing 63,648 items identified by the survey during the 20-year study period. Across NSW Aboriginal community housing, 84% of items repaired were routine maintenance issues. Faulty design or workmanship accounted for 11% of failures, with 5% of items fixed as a result of damage by the tenants

Figure 4. Percentage of items fixed under the NSW Housing for Health Program (n = 63,648) by the reason for repair from 1998–2017.

Focusing on tenancy management to reduce tenant damage will only address 5% of the issues related to house function in NSW community housing. Our results are consistent with previously published national data (2006) which showed, whilst there were slightly higher rates of tenant damage (10%), the primary cause for house function failure stemmed from a failure of maintenance regimes and quality control [9].

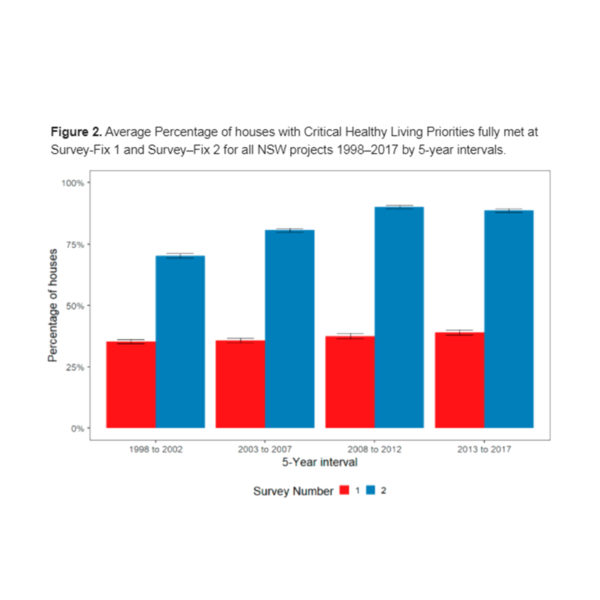

Figure 2. Average Percentage of houses with Critical Healthy Living Priorities fully met at Survey-Fix 1 and Survey–Fix 2 for all NSW projects 1998–2017 by 5-year intervals.

Although the average condition of houses at SF1 across all 112 HfH projects shows very little change over 20 years, (Figure 2) the 24 locations that have received a second HfH project have maintained higher house function (at the second project SF1) for most CHLPs (Figure 5), suggesting a sustainable benefit of the HfH program over time. This finding is consistent with results reported in the 10-year review which showed one community in 2003 where a third survey and fix had been undertaken 2–3 years later to gauge the sustainability of the program, house function had deteriorated slightly since SF2 (Survey Fix 2), but only 5% of the original funding was required to bring the houses back to the same

Figure 5. Percentage of houses with Critical Healthy Living Priorities fully met for NSW projects with repeat visits at First Project SF1 (n = 802) and SF2 (n = 722); and at Second Project SF1 (n = 788) and SF2 (n = 734) from 1998–2017.

For disadvantaged families where unemployment is high, the home environment is often the environment where people spend most of their time. Ensuring the homes’ ability to support health is associated with significant reduction in the rates of infectious diseases, which in turn can reduce the risk factors for many chronic diseases, such as renal and cardiac disease, both of which are overrepresented in the Aboriginal population [17,20,31]. The HfH program also helps ensure the home environment supports practices delivered by health messages through clinical and population health services. Improving health outcomes should reduce health expenditure on preventable conditions. “The cost of poor housing is borne by the health system” [32]

THE REPORT CONCLUDES – A lack of routine maintenance and faulty design or construction is overwhelmingly the key cause identified for the failure of items repaired under the program

The specification of quality health hardware in maintenance programs is likely to be a cost-effective investment in both housing and health in the long term

The program should be expanded to communities that have not yet received the program, and the program principles should be embedded into larger social housing repair and maintenance programs.

References

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health Fact File. 2006. Available online (accessed on 10 January 2020).

- World Health Organization. WHO Housing and Health Guidelines; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson, H.; Thomas, S.; Sellstrom, E.; Petticrew, M. The health impacts of housing improvement: A systematic review of intervention studies From 1887 to 2007. Am. J. Public Health 2009, 99, S681–S692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, H.T.S.; Sellstrom, E.; Petticrew, M. Housing Improvements for Health and Associated Socio-Economic Outcomes; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews: Glasgow, UK, 2013; Issue 2. Art. No.: CD008657. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, M. Housing and Public Health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2004, 25, 397–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Overview—OECD Economic Surveys: Australia; OECDD: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: www.oecd.org (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- Fletcher, M.; Guttmann, B. Income Inequality in Australia. In Economic Round-Up 2013; The Australian Treasury Social Policy Division, Commonwealth of Australia: Canberra, Australia, 2013; pp. 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Household Income and Income Distribution, Australia 2011–2012; ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Torzillo, P.J.; Pholeros, P.; Rainow, S.; Barker, G.; Sowerbutts, T.; Short, T.; Irvine, A. The state of health hardware in Aboriginal communities in rural and remote Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2008, 32, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Indigenous—Community Housing and Infrastructure Needs Survey (CHINS) 2006. 26 September 2005–15 November 2007. Available online (accessed on 5 February 2020).

- Nganampa Health Council Inc. Report of Uwankara Palyanyku Kanyintjaku: An Environmental and Public Health Review within the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Lands (UPK Report); Nganampa Health Council Inc.: Ciccone, Australia; South Australian Health Commission: Alice Springs, Australia; Aboriginal Health Organisation of SA: Alice Springs, Australia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, Q.C.E. Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody; AGPS: Canberra, Australia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- National Aboriginal Health Strategy Working Party. A National Aboriginal Health Strategy; Australian Government Printing Service (AGPS): Canberra, Australia, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sansom, B. The Camp at Wallaby Cross; Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies: Canberra, Australia, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Saggers, S.; Gray, D. Aboriginal Health and Society: The Traditional and Contemporary Aboriginal Struggle for Better Health; Allen and Unwin: Sydney, Australia, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bailie, R.; Stevens, M.; McDonald, E.; Brewster, D.; Guthridge, S. Exploring cross-sectional associations between common childhood illness, housing and social conditions in remote Australian Aboriginal communities. BMC Public Health 2010, 10, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council (AHMAC). Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Performance Framework Report; ACT; Office of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Health, Ed.; AHMAC: Canberra, Australia, 2008; pp. 580–586. [Google Scholar]

- Commonwealth of Australia Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Remote Housing Review: A review of the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing and the Remote Housing Strategy (2008–2018); Department of the Prime Minister & Cabinet: Canberra, Australia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australian; ABS: Canberra, Australia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Angus, C. Indigenous NSW: Findings from the 2016 Census; Statistical Indicators 02/18; NSW Parliamentary Research Service: Sydney, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Healthabitat. Housing for Health: The Guide; Healthabitat: Newport Beach, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pholeros, P.; Rainow, S.; Torzillo, P. Housing for Health: Towards a Healthy Living Environment for Aboriginal Australia; Healthabitat: Newport Beach, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lea, T. Housing for health in indigenous Australia: Driving change when research and policy are part of the problem. Hum. Organ. 2008, 67, 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthabitat. Healthabitat: What We Do. 2020. Available online: http://www.healthabitat.com/what-we-do (accessed on 5 January 2020).

- Robyn Kennedy Consultants P/L. Evaluation of the Aboriginal Communities Development Program Summary Report; NSW Government Centre for Education Statistics and Evaluation: Sydney, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Aboriginal Environmental Health Unit. Housing for Health. 2019 Tuesday 10 September 2019. Available online (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- Healthabitat. Housing for Health—The Seven Stages of Any Project. 2020. Available online (accessed on 14 February 2020).

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS Enterprise Guide Software; Version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows; SAS Institute Inc.: Cary, North Carolina, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Agresti, A. Categorical Data Analysis, 2nd ed.; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Aboriginal Environmental Health Unit. Closing the Gap: 10 Years of Housing for Health in NSW—An Evaluation of a Healthy Housing Intervention; Aboriginal Environmental Health Unit: Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2013. Rheumatic Heart Disease and Acute Rheumatic Fever in Australia: 1996–2012; Cardiovascular disease series; Cat. no. CVD 60; AIHW: Canberra, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, D. Presentation on the World Health Organization (WHO) Housing and Health Guidelines; University of Sydney Discussion Forum; Sydney, Australia, 20 February 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Colton, M.D.; Laurent JG, C.; MacNaughton, P.; Kane, J.; Bennett-Fripp, M.; Spengler, J.; Adamkiewicz, G. Health benefits of green public housing: Associations with asthma morbidity and building-related symptoms. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105, 2482–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colton, M.D.; MacNaughton, P.; Vallarino, J.; Kane, J.; Bennett-Fripp, M.; Spengler, J.D.; Adamkiewicz, G. Indoor air quality in green vs conventional multifamily low-income housing. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 7833–7841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, D.E.; Kelly, T.; Sobolewski, J. Linking public health, housing, and indoor environmental policy: Successes and challenges at local and federal agencies in the United States. Environ. Health Perspect. 2007, 115, 976–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonnefoy, X.R.; Braubach, M.; Moissonnier, B.; Monolbaev, K.; Röbbel, N. Housing and health in Europe: Preliminary results of a Pan-European study. Am. J. Public Health 2003, 93, 1559–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartram, J.; Cairncross, S. Hygiene, sanitation, and water: Forgotten foundations of health. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolf, J.; Hunter, P.R.; Freeman, M.C.; Cumming, O.; Clasen, T.; Bartram, J.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Johnston, R.; Medlicott, K.; Boisson, S.; et al. Impact of drinking water, sanitation and handwashing with soap on childhood diarrhoeal disease: Updated meta-analysis and meta-regression. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2018, 23, 508–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strunz, E.C.; Addiss, D.G.; Stocks, M.E.; Ogden, S.; Utzinger, J.; Freeman, M.C. Water, sanitation, hygiene, and soil-transmitted helminth infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fuller, J.A.; Westphal, J.A.; Kenney, B.; Eisenberg, J.N. The joint effects of water and sanitation on diarrhoeal disease: A multicountry analysis of the demographic and health surveys. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2015, 20, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mara, D.D. Water, sanitation and hygiene for the health of developing nations. Public Health 2003, 117, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clasen, T.; Pruss-Ustun, A.; Mathers, C.D.; Cumming, O.; Cairncross, S.; Colford, J.M., Jr. Estimating the impact of unsafe water, sanitation and hygiene on the global burden of disease: Evolving and alternative methods. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2014, 19, 884–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthhabitat. The National Indigenous Housing Guide: Improving the Living Environment for Safety, Health and Sustainability, 2nd ed.; Commonwealth, State and Territory Housing Ministers’ Working Group on Indigenous Housing—Australian Department of Family & Community Services and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Family and Community Services. National Indigenous Housing Guide; Commonwealth of Australia (AUST): Canberra, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- NT Department of Local Government. Housing and Community Development (DLGHCD). Healthy Living Practices. 29 November 2019. Available online (accessed on 9 February 2020).

- Long, S.; Memmott, P.; Seelig, T. An audit and review of Australian Indigenous housing research: Final Report No. 102; Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute (AHURI): Melbourne, Australian, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bailie, R.S.; Wayte, K.J. Housing and health in Indigenous communities: Key issues for housing and health improvement in remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities. Aust. J. Rural Health 2006, 14, 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steering Committee for the Review of Government Service Provision (SGRGSP). Overcoming Indigenous Disadvantage: Key Indicators; Productivity Commission: Canberra, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Telfar-Barnard, L.B.J.; Howden-Chapman, P.; Jacobs, D.E.; Ormandy, D.; Cutler-Welsh, M.; Preval, N.; Baker, M.G.; Keall, M. Measuring the effect of housing quality interventions: The case of the New Zealand “rental warrant of fitness”. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]