Pre-fabricated containers as refugee shelter: fit for purpose?

Concerned with the loss of basic health hardware and infrastructure in the temporary nature of building for refugee camps, HH has been receiving these anecdotal reports from an international aid worker.

Part One: Air conditions.

There is a growing trend in the use of pre-fabricated containers as transitional shelter solutions for refugees in camp contexts across Europe and the Middle East. In the evolution of a typical refugee camp, the population influx is housed in emergency popup tents and serviced by communal amenities and mass in-kind distributions of food, NFIs (non-food items) and needs-based medical assistance. Once the influx of new arrivals has subsided and should the camp continue existence beyond 6 – 12 months, these tents are replaced by more robust ‘transitional’ shelter that is transitory in nature; easily demountable or movable. Thus, the pre-fabricated container model has become an ideal tent replacement in camps; it is easy to mass produce, transport and relocate. However are they really a better solution for the health of families often living in these containers for years at a time?

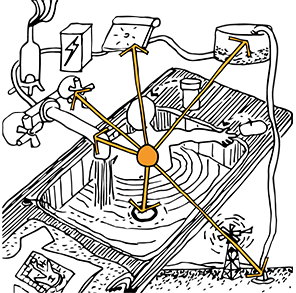

The containers donated to refugee camps are of the quality and standards typical to temporal office units, predominantly designed to serve as short term office spaces on construction sites. Thus, they are not built to handle long-term domestic occupation. They do not have the robust health hardware in place to ensure that residents’ health, safety and comfort are not impaired by their living environment. One major issue is the lack of appropriately designed ventilation systems for these containers, especially solutions that take into consideration the specific climate in which they are used.

In one camp, recent thermal data collection inside containers revealed that the average carbon dioxide levels varied between 700ppm to 1500ppm, with readings of up to 2500ppm. In general, 350 – 1000 ppm are typical CO2 concentrations in occupied indoor spaces where there is good air exchange. Between 1000 – 2000 ppm, people tend to suffer drowsiness and can feel the effects of inferior air quality. If an indoor space contains levels of CO2 above 2000 ppm, occupants are likely to suffer headaches, sleepiness, poor concentration, loss of attention, increased heart rates and slight nausea.

The data revealing this substandard air quality was collected during winter when people are more inclined to keep their windows closed to retain the warmth from their gas heaters, as well as to smoke indoors. Nonetheless, there should be systems in place to continue necessary air flow, despite the daily habits of occupants. The Housing for Health guide provides ample solutions; the use of cross ventilation, double glazing and convective cooling (venting of high level hot air to draw in cooler air from lower levels) to maximise night time cooling in summer (http://www.housingforhealth.com/housing-guide/controlling-the-temperature-of-the-living-environment/). The need to retrofit these containers in order to achieve satisfactory air exchange begs the question – why begin with these office containers as refugee shelters in the first place?