Reflections – Housing for Health on a NSW Project

Reflections from Dr Liam Grealy and Owen Kelly on a recent HfH project

Owen Kelly // Architectural Graduate

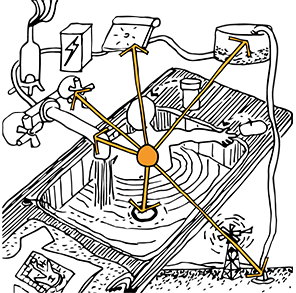

In April 2019, a crack team assembled in north-west NSW for a Housing for Health Project. The team included Environmental Health Officers, Academics and Architects but mostly it was made up of locals. Largely it would be these locals that would test, check and fix over 250 items per house in their own community. From testing hot water temperatures, fitting new shower roses and testing electrical power points. This is the tough, grinding, dirty and frankly exhausting work that is done to improve health through the living environment. This in Healthabitat terms is called “Survey/Fix 1” – meaning that whilst the teams are doing their FIX work they also SURVEY crucial data as to what state the “Health Hardware” of each house is in. This then forms the basis for all future work in the community, as each piece of “Health Hardware” is related to Safety and the Healthy Living Practices (HLP’s) which dictate the priority order for which jobs are done to have the biggest impact on health. For example, to prevent common infectious disease, it is more important to remove waste (shit) safely (HLP3) than to install an awning to a western window to reduce heat in living areas (HLP8).

Waste pipes from a bathroom under a house broken and spilling out onto ground near footings causing rot and destabilising the footings.

What struck me as simultaneously obvious and incredible was how the local teams worked. Employing local people works in several ways, firstly confidence and skills are gained in identifying and fixing the “health hardware” that is critical to health. Beyond this is how the teams navigated other locals and access into homes. By having local people on board, they know the ins and outs of who is home, where to find people and when and where to turn up or not turn up. The local teams were critical to the speed and efficiency of the project.

It felt less like work and more like being shown around town by an excellent group of tour guides, via a few plumbing issues and leaking shower heads. Bravo teams!

Self titled “A” team on HfH project.

Dr Liam Grealy // Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Housing for Health Incubator

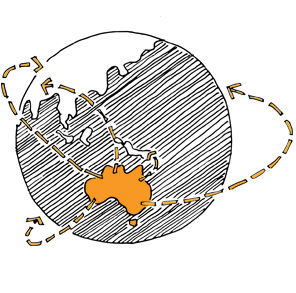

I’ve been asked to reflect on my first experience participating in a Housing for Health (HfH) project. After more than 238 projects across Australia and internationally, the potential for novel insights into HfH is somewhat narrow, especially from a first-timer. HfH is a tried and tested survey and fix methodology, refined across three decades, and shown by NSW Health (2010) to reduce hospital separations. Very few housing or public health programs could evidence such a claim about proven impact, reputation, and longevity. Indeed, in the Remote Housing Review (2017), published in advance of the conclusion of the National Partnership Agreement for Remote Indigenous Housing (NPARIH) in June 2018, the authors acknowledge the significance of repairs and maintenance work to government-owned Indigenous housing provision and the Housing for Health approach specifically: “the first priority for governments has to be to protect their investments and increase the longevity of houses by maintaining the housing already delivered. The key is an increased emphasis on planned cyclic maintenance, with a focus on health-related hardware and houses functioning.” In this moment, the challenge remains how to incorporate this proven methodology into state and territory housing departments beyond NSW Health.

Despite the complex logistics of coordinating multiple teams to survey over 100 houses, while employing and catering for about 25 staff, the work was rolled out incredibly smoothly. In this instance my perspective only captured stage 4 – Survey-Fix One – which follows the prior stages setting up the project – project planning; community negotiation; and feasibility report and budget preparation – and precedes the more extensive fix-work and capital upgrades, Survey-Fix Two, and reporting back to the community. Survey-Fix One is perhaps the “main event”, where team members including community residents and environmental health officers donned our yellow hats and surveyed the health hardware of houses included in the project, fixing items as we went. A dynamic approach was required, with word-of-mouth determining our crisscrossed path through town depending on who was at work or at home. The participation of community members is not simply ideal but fundamentally necessary to the success of the project: as educators to those of us from elsewhere, as familiar faces to and translators for other residents, for their technical skills for fixing health hardware, and for their knowledge about where we should head to next.

A hot water relief valve re-directed under the house instead of being safely finished and accessible.

Healthabitat’s data set and its image archive provides broadly accurate representations of the condition of the houses in this project. As in all communities, houses were highly variable, with some passing almost all the over 250 items assessed within the checklists and others requiring more significant attention. Working through our sheets, we tested and identified blackened or sparking powerpoints, replaced light bulbs and marked failed light fixtures for the electrician to attend to both in the subsequent days. We checked drainage, hot water systems, taps and faucets, cisterns, laundry tubs, and all those other items which determine residents’ abilities to enact critical healthy living practices such as washing people, washing clothes and bedding, and removing wastewater safely. We variously identified instances of mould, rust, leaks, and rot, as well as absent insulation, broken stoves, missing smoke detectors, and exposed wires. Instances of bathroom PVC piping draining straight under houses or hot water system relief values cut dangerously high were not uncommon – anecdotal instances resembling Healthabitat’s findings for the key reasons for health hardware dysfunction: poor initial construction and a lack of routine maintenance. As Stephen Graham and Nigel Thrift (2007) write, “Architectures are morphogenetic figures forged in time, tacking against a general entropic tendency.” Over time, things wear out, break, fall apart. Without careful mediation, this process accelerates.

Waste pipes from a bathroom have no connections to a waste treatment system under this house. Meaning water from wet areas pools under the house, rotting, rusting or weakening house foundations and providing habitat for mosquitos to breed.

The Housing for Health Incubator, partnered with Healthabitat, is exploring the barriers to seeing the Housing for Health methodology incorporated into state and territory approaches to the management of public housing stock, replacing housing repair programs that are not evidenced for improving health outcomes, less extensive, and applied inconsistently or reactively. Although the positive health and infrastructural impacts of planned, recurrent R&M have been clearly demonstrated, government housing programs often prioritise new builds and major refurbishments. Tess Lea and I call this the “assembly fetish”, a perspective that reduces housing crises to the problems of new builds and land release, and in which attention to codes and standards is inconsistent – it is at the planning, promising, and pre-handover stages that construction is scrutinised, while from the post-occupancy stage householders become the objects of surveillance and superintendence. Maintaining a house that allows residents to enact healthy living practices is not an easy feat, contending with environmental, political, and institutional factors that coalesce to pull housing assemblages apart. For me, participating in a HfH project demonstrated directly the ongoing fixwork required to maintain functional health hardware, the need to arrest major failures before they occur, and that the HfH methodology deserves further promotion for wider take-up.