Policy tips & drink coasters

Not too long ago, a Federal Housing Minister informed staff that the ideal policy briefing should be able to be written on the back of a drink coaster. HH is not sure what this says about the Minister, the calibre of staff, concise writing skills or the size of drinks coasters but we are adopting the approach in the lead up to the next Federal election in Australia.

Each week up until September, we will be introducing a new policy tip, Short concise and written by two highly skilled pencils. One is a 2B, a softer pencil good for broad-brush thinking and the other a 4H, a fine and hard pencil…sharp and precise. A good mix for policy development.

This week’s latest policy…..

COASTER POLICY #10

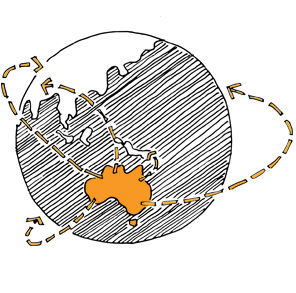

Indigenous housing quality, local employment and cost – A call for an independent enquiry into the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing

For almost 4 years HH has been asking the most basic questions about the quality of design and construction, local indigenous employment and costs of the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing. There have been no answers from the Federal or State/Territory Governments. Amnesty International also asked similar questions and received the standard form letter saying all was going well.

Why has NO party asked similar questions of a $5.5bn program that is already half spent? The ‘pink-batt’ insulation program is now the subject of a judicial review if one side of politics has its policy way. The Building the Education Revolution received a solid press workout and investigation. Why no direct questions about a stated national budget that can’t connect houses built and upgraded with the total money spent, gross building faults observed and documented, no quality assurance program open to scrutiny and no details of the type and longevity of indigenous employment.

Why then has there not been a peep from the press, professions or political parties on this program? Some thoughts:

- Indigenous issues are never election winners or losers

- the work is remote and does not impact daily on suburban mums and dads like insulation or education programs

- the work is remote and will never be seen by most Australians, out of sight out of mind

- if the work fails or is poorly built … the tenants can be blamed for damaging the houses

- if the costs are high …blame remoteness

- the program was really about delivering large cash injections to regional and remote areas of Australia and never had a real concern about indigenous housing

- and finally, in these days of massive national wealth, maybe $5.5bn has become small change in Australia – not worth even investigating.

The policy – call for a full, independent enquiry into the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing with representatives with expertise in remote indigenous communities, the building industry, remote housing design and building economics. The enquiry should have a maximum duration of 6 months so that some of the remaining money can be better spent.

COASTER POLICY #9

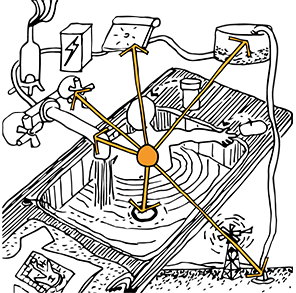

Power and health

If you live in suburban Australia power costs and bills are an unpleasant fact of life. We need energy in our living environment to live and combine solar, electric, gas in all sorts of combinations to meet our needs.

Energy saving increases with power costs and the introduction of smart meters to allow better control of power use, home solar systems and a range of energy saving appliances with known energy star ratings are now common.

Rural and remote Indigenous community residents are living in houses provided by state and federal government money that have the highest energy using hot water systems, cooking appliances and lights. They are often poorly insulated and designed and have no cooling systems provided (apart from fans in some parts of the tropics. To cool (or heat the houses in cooler climates) therefore takes large amounts of energy.

And it will come as no surprise that energy costs are much higher than in urban and suburban Australia.

HH has done many applied research and development projects on how water systems, cooking appliance, lights and heating/cooling to prove that energy use can be dramatically reduced using better products and design.

But most of these energy saving products, ideas and design ideas, regularly used in mainstream Australia, have been ignored by public housing providers. It much easier to do very little and deflect the problem with statements like:

- ‘these products or design ideas are too expensive’ (ie the capital cost is initially higher but whole of life cost may be significantly lower) or

- ‘the tenants will just waste energy anyway so it makes no difference’ (ie we are too lazy to do our jobs as designers or housing managers and it is easier to blame the tenant)

The end result of doing nothing is that now, more and more people are having their energy supplies disconnected as they struggle to pay bills and the houses deliver less and less health benefits to the tenants. Instructing people on energy saving may have a place but only AFTER fundamental improvements in the equipment and design of houses.

The policy? Poor people must be provided with better technology and design than the wealthy. Power use and reducing the need for energy in houses is a good place to start.

.

COASTER POLICY #8

Water water everywhere and a not a soul who thinks!

Water is an essential part of at least 8 of the 9 Healthy Living Practices. Water is essential for life and Australia is the driest continent on earth.

Water management, particularly in rural and remote Indigenous communities, has always been seen as problematic. A common and pervasive myth has been that water wastage by community members is the key water management issue.

HH has kept water use data for over 20 years and the results have always shown similar issues related to water use –

- failed house fittings – such as tap washers, toilet cistern seals and mineral salt affected valves – are a high cause of water waste

- leaks from in-ground pipes supplying the houses and community buildings are the next big water waste point

- when the leaks are fixed, the ‘real’ water use in an Indigenous community approximates about half the average water use of a non-Indigenous community (as measured per person in households)

Given this, why then are education campaigns with posters, stickers, fridge magnets and clever jingles about water saving always the first action of state and federal governments?

A recent water project in an Indigenous community saved around 80% of water used by fixing leaks, using local community members as the fixers, before it was stopped without warning by the responsible Federal Government department. Perhaps proving that the infrastructure, rather than the people, was the problem puts too much pressure on departments to actually deliver working infrastructure.

HH survey data of 7,700 houses nationally showed that only 43% of the houses had a water meter. How can water be managed (at the house level) without any means of measuring water use?

The policy? First – fix leaks, add water meters to houses, main supply points and branch lines within communities. Then, in a polite voice, ask Indigenous communities to prepare educational material aimed at instructing non-indigenous people about saving water.

COASTER POLICY #7

There’s more than one way to reduce the negative health impacts of crowding.

Current Federal government policy goes further than many previous policies over the last 25 years to reducing unwanted crowding in housing. The problem is the Federal government does not understand its own policy, and neither do the states implementing the policy on the ground.

They are still governed by the basic principle that more houses will equal less crowding.

25 years of HH work has shown this is rarely the case. Simply building more houses does not reduce crowding levels. Assessing the effectiveness of programs by the number of houses built will not reduce crowding.

Houses with services that do not work cannot be used and then people move to share the resources of the house next door, increasing the real levels of crowding. Crowding will be reduced by more functioning houses … the detail is important.

COASTER POLICY #6

Making change is possible…without a huge budget

Too often policy is seen as a commitment to spend money. The more money spent, the bigger and better the policy. Well HH will put forward the small drink coaster idea that maybe the measured results of a given policy, say for example the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing with $5.5bn being spent, are the real measure of policy success.

Hard to imagine the press release “Small amount of money to be spent very carefully and results will be assessed be known, clear and unchanging criteria before committing more money”

An independent review of 10 years of Housing for Health in NSW was independently assessed by the NSW Department of Health and they found a 40% reduction in hospital separations after spending approximately $11,000 per house. Rather than being lauded by the NSW Government and held up as an example of considered, economically responsible work, it was released with little fanfare for fear it may start questions about what money is spent on other programs and what are the results.

The Australian Government response was even more muted. NONE! The work demonstrated the link between the Healthy Living Practices, functioning houses and measurable health benefits but NO RESPONSE.

The actions of the Australian Government, in concert with the states, since 2009 have produced housing that avoids all the evidence provided in the National Indigenous Housing Guide, the Healthy Living Practices and the results of the health review. So far around $2bn is estimated to have been spent but no one knows the real figure. So as the halfway mark is approached the big policy keeps spending money.

The housing function (as measured by HH) is poor, health results in the future (if they were ever carefully assessed) will show no benefit to the residents. but in the not too distant future, the public will be shown a grand and generous policy that spent $5.5bn on remote area Indigenous housing.

The Australian Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, started a Commission to oversee the roll-out of the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing. There was a public mandate and a broad range of skills on the Commission.

The Commission was ‘dissolved’ after the then PM Rudd was rolled in 2010, and, when the early results of the program were questioned by all the independent Commission members. With $3bn still to spend perhaps it is time to review the policy and put the results on a drinks coaster…HH has a few ideas and would be happy to help.

COASTER POLICY #5

Housing quality versus the political numbers game

It seems so, so obvious that the roof should be on the top! The beer coaster policy tip may exaggerate the point… but only slightly. The National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing has proudly boasted program numbers of new houses built and houses upgraded whilst delivering mediocre designed and poorly functioning houses.

Numbers are fine, HH often collects and uses numbers to tell housing stories but WHAT numbers is the important part.

Current numbers, based on over 7,800 houses tested national, show only 35% of those houses have a working shower. The number is not that a house has a shower but that it works.

Numbers showing houses built may prove that there is a roof, a floor and a shower but NOT that these contribute to the health and well being of the occupants.

The 9,000 houses, that will be delivered by the $5.5billion National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing program, are all being built in remote areas away from the scrutiny of the press and media. They are being built for the poorest people in the country who have the quietest voices to protest if the floor is not on the bottom or the shower does not work.

Any national housing policy should focus not on ‘build numbers’ and the location of the roof (on the top) but on the more complex and important issue of ongoing house function and its contribution to the lives of those living in the house.

COASTER POLICY #4

The cost of remote indigenous housing in Australia

Yes, building housing is expensive. Housing that works and continues to work to deliver health benefits to people over 25 years involve not just capital cost but also running costs, management and maintenance costs.

When the past and previous Federal governments put forward plans to spend $5.5 billion to build 4,200 new houses and upgrade 4,800 houses in remote Indigenous communities nationally who could complain? This could make a huge difference to the lives of people.

When the first $$ were put against the targets ($450,000 per new house on average and $75,000 for an average upgrade) the budget suddenly made no sense. Take your pocket calculator or phone and do the sums!!

Is it possible that well over 50% of the budget is being spent on overheads and on-costs above and beyond normal builders margins? If not, where is the money going?

A recent press release from the Federal Government produced the results of a review of the national program which stated that the first year of the program was lost due to delays but since then the program has delivered over 5,000 upgrades in less than half the estimated program time. Surely this has to raise questions about the goal, the quality of the product delivered and the costs.

A clear and believable statement of program scope and all costs, not just house building capital costs, should be a key part of any housing policy.

COASTER POLICY #3

The ‘culturally appropriate’ house design.

Whenever Indigenous housing design is raised, the words ‘culturally appropriate’ are not far behind.

No one could disagree that all house design should be culturally appropriate but what defines ‘culturally appropriate’.

Some learned academics and practitioners have spent decades defining ‘culturally appropriate’ design and have explored areas such as design process, consultation methods, local design and build, an environmental health model, a sociological model and using design post-occupancy evaluations to asses the results.

HH supports any work that dispels the myths that proliferate in this area and leads to better house design.

The most common myths that impact on housing starts by lumping all indigenous people into one group, as if there is a universal person…the design victim. Next, come the broad statements that quickly become woven into housing policy – one thread fact one thread fiction. The myths sound a bit like this:

- “Damage, by the tenants, is the main factor to be designed out through stronger, tougher building parts.

- Indigenous people don’t want housing and should be allowed to live without housing…on the land

- The only housing people will respect is housing that is built by the residents themselves

- Simple buildings are best – plumbing and electrical systems add cost and complexity that is not really wanted – if houses are simpler they are cheaper and all people can have a house

- More houses will reduce crowding so we need to build cheaper houses and more of them

- Rectilinear buildings are not culturally appropriate

- Houses should be very large to reduce crowding

- Houses should be built very close together without fences as people like to share and live together

- Housing should be flexible so the residents can change them if they wish”

HH proposes some basic, universal principles called Safety and the nine Healthy Living Practices as being culturally appropriate. The design solutions may change in every place, but unless the principles are achieved, poor health and illness will deplete any culture and that is not appropriate.

‘Culturally appropriate’ housing will include working showers, toilets and kitchens. This will involve good consultation, design, specification, construction, maintenance and management. Given the current national performance noted by HH in over 7,500 houses, functioning houses that provide some safety and health benefit to residents would be revolutionary.

This would be ‘culturally appropriate’ and should become policy.

COASTER POLICY #2

The myth of the perfect house design

For the last 28 years, one of the most common questions asked of HH is “What is the perfect house design for indigenous people?”.

The question comes with varying tones:

– at the public talk, the tone can be optimistic…’ if you know all of this then you must know what the perfect design is?’

– in the state capital … ‘well smarty pants if you know so much what is the perfect house design that will cost 30% less and be maintenance free?’

– in the national capital … ‘either give us the perfect house design which can be reproduced nationally for $2.50, have zero maintenance, use no energy or water and solve indigenous employment or you will be counted as one of the opposition and shot!!’

Over the years the core ideas surrounding Indigenous housing have been:

– one size can’t fit all but… if we could find the one perfect design it will be cheaper and all will benefit

– the house must be indestructible -based on the now refuted myth that Indigenous people trash houses

– any new brilliant house design will cost very little

– Indigenous people should build the houses, regardless of the design, as this will ensure they value the houses. No evidence has ever been produced to prove this idea

– Indigenous people should own their houses, regardless of the design, as this will ensure they value the houses. No evidence has ever been produced to prove this idea

– any design for Indigenous people should not be square or rectangular in plan as this is a western construct not culturally appropriate … who has decided this is never quite clear?

In recent history, a five-sided timber framed ‘yurt’ (called the Aussie Battler model) was secretly proposed as the universal solution for Indigenous housing nationally. Enquiries were made with the manufacturer to see if a few thousand could be produced quickly. It had no internal linings, no shower, toilet, kitchen or laundry, no electrical wiring or insulation but it did have a door and a window. It ticked all the boxes:

- low energy use (no electrical system)

- low water use (no plumbing system)

- super cheap and hence affordable

- so affordable it could be affordable to even the poorest Indigenous family through a government arranged mortgage

- it was able to be bolted together on-site by unskilled Indigenous worker

- it was almost indestructible – except from fire and termites as the timber was not termite resistant

It went very, very close to being implemented by the Federal Minister keen on the idea and a complaint department. This would have been a very bad national joke at the expense of the public purse but more dramatically the health of those forced to accept this ‘perfect house design’.

Any serious policy on any housing must start with the well being of the residents and the place where the house is built at the core.

This will require resident involvement, great design skill, knowledge of past mistakes and achievements in the design of housing, good financial modelling and a greater emphasis on the 50-year house cycle including maintenance and management cost …. not just an obsession with the house as object and short term capital cost.

COASTER POLICY #1

Linking Housing and Health policy.

You would think this was an obvious thing to do. However, despite hard evidence produced by an independent state health department, the current Federal government is distancing itself from links between housing and health. Proving that large sums of money have been spent building new houses or upgrading houses is far, far easier than proving houses function and improve the lives of people. The proof of this separation of housing and health?

- In 2011, the national Fixing Houses for Better Health program, that had been operating for 12 years, was stopped by the Federal Government. FHBH showed the health performance of houses before and after fix work and linked housing to health. Read the independent review of FHBH here.

- The quiet dismantling of the National Policy Commission on Indigenous Housing in 2010. Established by Prime Minister Rudd in mid 2008 the Commission was to oversee the rollout and results of the National Partnership Agreement on Indigenous Housing. The health link to the national housing program was stated and involved the inclusion of a Healthabitat director on the Commission. Where is it now? Who knows the results of the national housing program?

- failing to review the National Indigenous Housing Guide that specifically links housing and health. Due for review in 2009, no work has been undertaken to update the Guide, or have newly built or upgraded housing comply with the third edition of the Guide. The Guide was first published in 1999 and was reviewed and updated twice into the current third edition, released quietly in 2007.

Given the trends since 2007, we think a linking of housing and health policies would be… revolutionary!