Disaster looming – the end of NPARIH

Minister Nigel Scullion and the Australian Government appear to be ignoring their own 2017 review into the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing (NPARIH). Rather than increasing critical funding for remote Indigenous housing, they are talking for the first time about completely walking away.

On 12 February 2018, Senator Patrick Dodson asked Minister Scullion in parliament whether his government had “taken a decision to end the decade-long Commonwealth investment in remote Indigenous housing agreed in the National Partnership Agreement on Remote Indigenous Housing.”

Mr Scullion replied that the Federal Government would be moving away from a national partnership in favour of a bipartisan approach, and that the only commitment currently being negotiated was $120 million to remote housing in the NT, which the NT would match.

Most of the debate on funding is for new house builds. Whilst this is important, what is lost in this debate is that if NPARIH funding is cut the biggest and most immediate health impact will result from an end to funding for ongoing cyclical repair and maintenance of existing houses.

It is well known that State and Territory Governments do not have the money to fund the high cost of maintaining remote Aboriginal housing on their own. This was recognised by previous governments and is one of the principal reasons why NPARIH was implemented.

If the Commonwealth withdraws NPARIH funding there will be dire effects on the ‘Closing the Gap’ commitments, and the health of Aboriginal people across remote Australia. The extraordinary funding investment made by the Australian people over the past 10 years towards building remote housing and improving health for Aboriginal people will have been for nothing. The improvements in levels of crowding celebrated in the recent Remote Housing Review into NPARIH will soon disappear. In a previous article ‘Solutions to Crowding’ written during the early days of NPARIH, Healthabitat warned that building new houses alone WILL NOT reduce crowding.

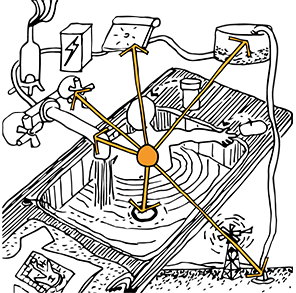

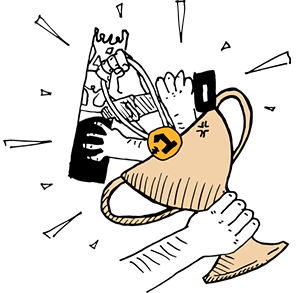

Images from left: Water quality not factored into specification of plumbing in remote housing, Housing for Health local team repairing health hardware.

With no cyclical repair and maintenance program, when someone’s toilet blocks it will not get fixed. Drains will overflow, kids will be playing in raw sewerage and rates of infectious disease amongst Aboriginal people will be plunged back to where they were in the 1980’s. What Healthabitat has learned over the past 30 years, is that routine cyclical maintenance of health-related hardware is critical in reducing high rates of infectious disease.

Successive Australian governments recognised this. Almost twenty years ago Federal Minister for Families and Community Services Jocelyn Newman MP stated;

“The lack of regular maintenance means that houses break down prematurely, and their life spans are short. These factors have contributed to environmental conditions that have a detrimental impact on the health of Indigenous people, especially young children.

When houses fail to function, particularly the housing components essential for good health such as water, waste removal and power facilities-the ‘health hardware’-a range of serious health problems can result. Breakdown in health hardware poses threats to safety, and has contributed to the high incidence among Indigenous people-especially children-of such conditions as skin and eye infection, diarrhoeal disease, respiratory illness and hepatitis.”

Minister for Families and Community Services Jocelyn Newman, National Framework for the Design, Construction and Maintenance of Indigenous housing, September 1999

In May 2001 Senator Amanda Vanstone and Minister Philip Ruddock MP declared in a joint statement that;

This Government is keen to bring a halt to the ‘build and abandon’ approach to Indigenous housing.

Inadequate housing is linked to poor health in indigenous communities, a problem the Government is determined to address.

The standard of housing and essential services in many indigenous communities is poor and this causes health problems and especially contributes to the spread of infectious diseases among children.

The financial burden on primary healthcare if funding is withdrawn for routine cyclical maintenance of remote housing will be immense. In 2012 NSW Health produced an evaluation into the Housing for Health program – a program that surveys and fixes critical health hardware in community controlled Aboriginal housing across NSW. This evaluation found that:

“Those who lived in properties where the Housing for Health intervention was implemented had a significantly reduced rate of hospital separations for infectious diseases – 40% less than the hospital separation rate for the rest of the Rural NSW Aboriginal population”.

Closing the gap: 10 Years of Housing for Health in NSW: An evaluation of a healthy housing intervention, August 2012.

Yet in 2018 the Federal Government may withdraw funding from the programs that put into practice everything that we know and have learnt over the past 30 years about the link between functioning health hardware and good health. If in June this year the Australian government walks away from funding of routine cyclical maintenance of remote Indigenous housing, the result will be catastrophic for the health of Aboriginal people across remote Australia.