Asbestos fibres and the impact of the new public housing model

A note sent to HH from Central Australia highlights not just asbestos risks, but how these risks have increased with the change in the control of Indigenous housing.

For the past 6-7 years, progressive Australian Governments have stripped power and control of housing from Indigenous Community Housing Organisations (ICHOs) and handed this control to State and Territory governments. This has been a clear move from community or social housing to mainstream public housing. As social housing has been promoted for non-indigenous people in Australia, the public housing model has been rolled into, or over, Indigenous communities.

This major change has not been based on hard any evidence of housing success or failure but rather on the ‘known truth’ that governments can manage Indigenous housing better than any community based organisation. Over 29 years of working in Indigenous communities and seeing the impact of many and varied state, territory and national governments compared to the work of the ICHOs, HH would strongly dispute, with hard data, their varied impacts on housing performance.

As all the states and territories have recently seen large sums of housing money headed towards their departmental coffers, they can only agree with the Australian Government and the change towards the public housing model.

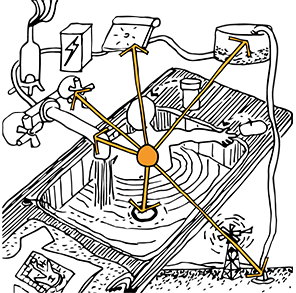

If we take a specific issue – the management of asbestos in houses built in remote communities – we see some the impact of the these changes.

Read the letter sent to HH and make up your mind about who will answer the questions that are posed at the end of the letter!

Asbestos on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands

In the APY Lands (in the north west of South Australia) the most common form of asbestos is chrysotile commonly found in the fibro cladding used on some houses.

Many of these buildings predated Land Rights and were either built by church bodies or by governments.

Under the Land Rights Act all fixed assets belong to the land holding body and as such their liability also rests with the Land Holding body.

When the houses on the AP Lands were under the control and management of the land holding body an Asbestos Register was in place and regularly updated. This Indigenous Community Housing Organisation (ICHO) managed all the houses on the APY Lands that were occupied by indigenous people irrespective of their geographic location.

Now that housing has been taken off this ICHO and mainstreamed into state managed public housing there is no Asbestos Register in place. It also appears that under a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU), houses on “homelands” are not the responsibility of the state based public housing entity.

Houses continue to be identified as containing asbestos products. Some of these are situated on homelands and as such responsibility for the safe removal of asbestos becomes a contentious issue.

Once these issues of responsibility are resolved and removal of the asbestos takes place, in many cases, this asbestos material finds its way into the local landfills none of which are licenced for accepting hazardous waste.

As these landfills are designated worksites, they are subject to the new rules governing asbestos that came into force in January 2014.

An Asbestos Management Plan and an Asbestos Register must be in place and be regularly reviewed and updated. There are also a range of other new requirements.

Public Liability policies appear to have an absolute exclusion for any injuries resulting from asbestos exposure. Workers Compensation policies could well still provide some cover for workers affected by asbestos exposure.

Things to check:

• Is there an Asbestos Register and an Asbestos Management Plan in place?

• Are all houses covered by the Register and the Plan?

• Are all local landfill sites designated as ‘hazardous waste’ landfills?

• Are all the organisations who operate in an environment where asbestos has been found to be prevalent aware of the new rules for dealing with asbestos that came into force on January 2014?