EDUCATION: UoN ‘Hot House’ studio recap – Dr Jasper Ludewig

‘Hot House: Heat, Health and Energy Insecurity in Indigenous Housing’ UoN semester recap.

Dr Jasper Ludewig and students write a recap of the semester-long studio, project focus and student learnings.

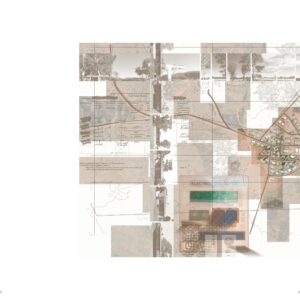

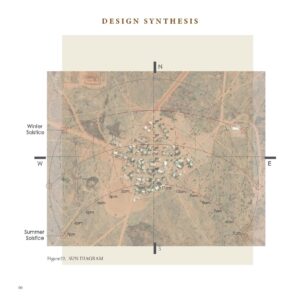

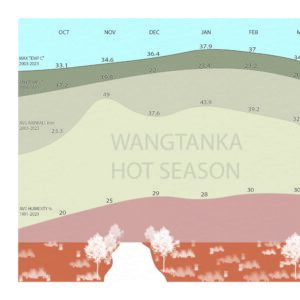

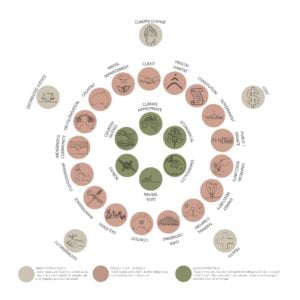

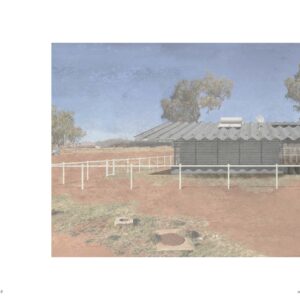

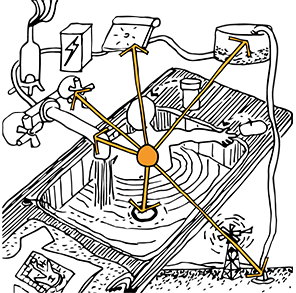

Student work extracts of site analysis (click to enlarge)

Overview (written by Dr Ludewig and students)

In semester one of this year, we participated in a live research cluster in the Masters of Architecture at the University of Newcastle that focused on questions of heat, health and energy in remote Indigenous housing. Working together with Healthabitat over fourteen weeks, we were asked to research and develop viable and cost-effective proposals for mitigating heat gain in the remote Northern Territory.

In response to the brief set by Healthabitat, we developed research-led proposals for a standardised “kit-of-parts” that could be applied to existing housing to mitigate heat gain and energy insecurity. Proposals were based on detailed analyses of the shortcomings in the existing housing stock (typically concrete blockwork construction lacking insulation, roof ventilation, shading, air-conditioning, guttering and solar panels), and the wider conditions of remote Australia where energy, food, transport and labour costs are often many times higher than anywhere else in the country. In his project report, fifth-year student Lochlan Southgate explains how these factors combine to entrench the effects of heat on health in the remote Northern Territory:

Energy insecurity occurs more often, houses are disconnected from power at a larger rate and communities are forced to pay higher prices, leaving cooling as a last option. Crowding further exacerbates the issues around heat and health: with a lack of adequate housing, people are forced to share more of the housing stock, which intensifies discomfort and raises internal temperatures within homes.

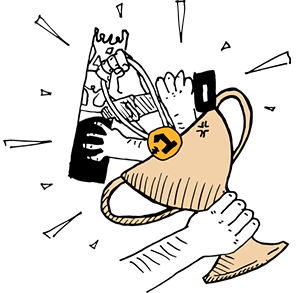

See the compilation of work and thinking by two students here on ISSUU.

Further details of the semester and student work (written by Dr Ludewig and students)

Extreme heat events are becoming commonplace in summer months worldwide, leading to increased mortality rates, hospital admittance, chronic disease, adverse birth outcomes and healthcare costs. Meanwhile, the Northern Territory is already living with a changed climate, experiencing unprecedented annual increases in the number of days above 40°C each year. Writing about Central Australia, medical professionals and researchers frequently refer to the “critical levels” of excessive heat, poor housing and energy insecurity as key factors in an imminent health “catastrophe” that threatens to displace Indigenous people from Country as climate refugees.

Each week we were joined by practitioners and researchers to further elucidate the full dimensions of the project brief. Dr James Smallcombe and Dr Grant Lynch from the Heat and Health Research Incubator at the University of Sydney invited us into their climate chamber to simulate the experience of everyday life in extreme heat. Andrew Broffman from the Fulcrum Agency discussed the importance of evidence-led design in thinking about the capacity of architecture to address what are, fundamentally, questions of public health. Professor Tess Lea from the University of British Columbia provided an overview of her co-authored Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute report, Sustainable Indigenous Housing in Regional and Remote Australia (2021), encouraging us to engage with the performance of existing remote housing as a pressing technical problem rather than waiting for policy fixes and program rollouts. Dr Simon Quilty, presenting his ongoing project with Norman Frank Jupurrurla and Office, Wilya Janta (Standing Strong) Housing Collaboration, made the argument for a housing model that exceeds mere health performance to also encompass quality of life and aesthetic experience more broadly.

Weekly readings and seminars extended the contributions made by these guests, outlining the legal loopholes that lower and/or suspend construction standards and consumer protections for Indigenous communities; the austerity logics of governments when it comes to service provision in remote settings; best-practice specification and procurement models; and the fact that contemporary Aboriginal housing needs to be understood as one of the infrastructural legacies of colonialism—the repeated failure of which is already baked into the chronically underfunded conditions in which it is erected. As fourth-year student Caitlyn Sherwood observes in her final project report, houses in remote communities are often unliveable because the government:

does not provide adequate health hardware specifications, or buildings that respond to their environments, or buildings that are created with the concept of longevity. The houses are often not built to the minimum construction codes and standards that the remainder of the country adhere to, and often the cheapest and best upfront value items are installed. This creates a home which will undoubtedly fail, if not due to [environmental factors] then through poor quality fixtures, fittings, construction and installations that have no scheduled maintenance.

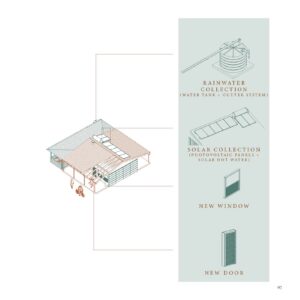

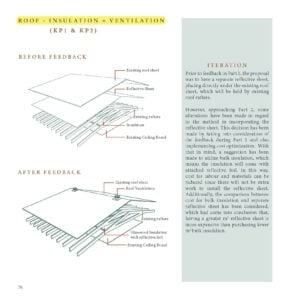

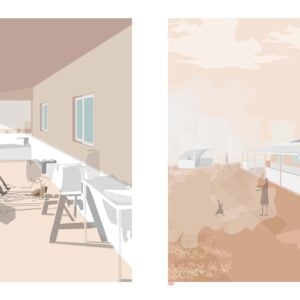

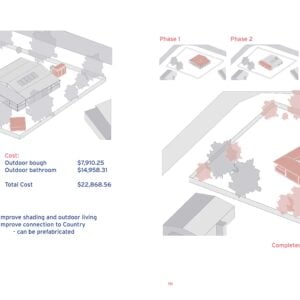

In addition to tackling the aspects of the brief mentioned above, proposals also needed to be costed and designed in keeping with Healthabitat’s survey-fix project methodology. We focused on robust, Country-guided and climate appropriate strategies for insulating, ventilating and increasing the functional space of existing housing, as well as the opportunity presented by the yard to extend the living space of each dwelling. Adopting the language of Healthabitat (and Fred Hollows), each element of the kit-of-parts was understood as “health hardware” that needed to be extensively researched. Specific solar panels, solar hot water systems, gutters and rainwater tanks were all approached as tools for increasing resource security and promoting active cooling by reducing cost. Planting, garden mounding and low-maintenance shade structures were likewise devised to exploit prevailing winds and to protect key living areas.

As the critical geographer Neil Smith famously argued, global capitalism always tends to develop unevenly, favouring certain geographies over others in its distribution of value and resources between different groups of people, especially during moments of instability and crisis. “Not only does capital produce space in general,” argues Smith, “it produces the real spatial scales that give uneven development its coherence.”[1] As climate change continues to destabilise who gets to live where and on what terms, architects must understand how their particular skillset—and the labour that sits behind it—can meaningfully assist communities in resisting the broader forces of uneven development. From coating roofs in abrasion-resistant, light-coloured paints, to half-height external insulation systems; and from cost-saving techniques for prefabrication and trucking of construction materials, to maintenance schedules attuned to the seasonal change of Country, this research cluster has revealed to us the potential for the architecture profession to contribute to this important undertaking. We are grateful to Healthabitat for their invitation, time and generosity, and look forward to seeing how this research informs their work in future.

- sdsg

- sdgsg

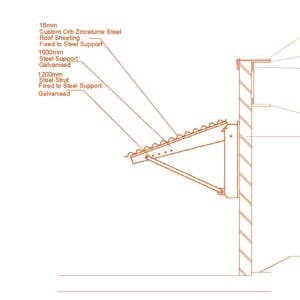

Student work extracts of design development, technical details, project stages and costing (click to enlarge)

[1] Neil Smith, Uneven Development: Nature, Capital and the Production of Space (London: Verso, 2010), 7.

Bonanta Adity, Quinton-Albert Cannataci, Apporva Chauhan, Haiyun Dai, Janet Domdom, Sina Elyasi, Kate Hackket, Qian Li, Jialiang Luo, Aliah Mohamad Rizam, Caleb Nixon, Brayden Rand, Caitlyn Sherwood, Min Khant Sithu, Lochlan Southgate, Saba Tamadoni, and Dr Jasper Ludewig.

Thank you Dr Jasper Ludewig for collaborating with us on this studio. This studio has taught greater awareness about the important impact of health hardware and routine maintenance on health, particularly for these architecture professionals at such a formative stage of their education and careers. Thank you to all students for your hard work.